The Martin Luther King Jr. Library is filled with more than just books. With a little searching, residents can find historical artifacts, niche technologies, a comprehensive chronicle of the city’s history and more.

The Martin Luther King Jr. Library on G Street in Chinatown is a wonder. Since it was built in 1972, it has operated as the District’s central public library branch and served as a free educational resource for hundreds of thousands of District residents.

But the walls of this historic landmark are lined with more than just books. Here are seven wonders hidden throughout the library’s halls and locked away in back rooms.

Historic DC Documents and Artifacts

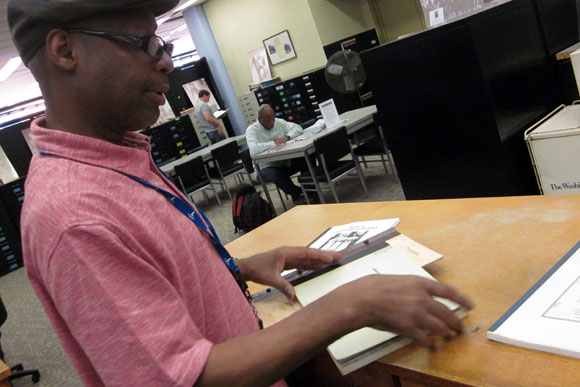

Special collections librarian Kenneth Despertt mans the desk at Washingtoniana. Despertt's unit contains exhaustive records on district's history, encompassing maps, real estate records, business registries, genealogical records and others. "We don't

Special collections librarian Kenneth Despertt mans the desk at Washingtoniana. Despertt's unit contains exhaustive records on district's history, encompassing maps, real estate records, business registries, genealogical records and others. "We don't

In 1942, the DC Central Library went on a bit of a shopping spree, reaching out to collectors and buying up historical artifacts related to the city’s history. It acquired scores of letters, maps, documents and other rare baubles, like a service hat from a uniform worn by a Tuskegee Airman.

The library owns what it believes to be one of the earliest public education documents in the nation’s history, signed by Thomas Jefferson in 1805. The document is a written pledge by some of nation’s top gentry – James Madison and Henry Dearborn, among others – to donate funds to establish a public education system for the District. While Jefferson was President, he developed the pledge to entice rich and poor residents alike in the District to donate funds, promising the federal government would match each dollar. Mark Greek, special collections coordinator, says the document was notable for starting what would eventually become D.C.’s public school system, and it stands as one of the earliest examples of a public-private partnership model that still funds many universities and educational institutions today.

Greek said the library no longer has the budget to purchase new items and relies almost entirely on blood, sweat and donations to convince current collectors and public figures to keep them in mind when their estates decide to donate. If the collector doesn’t have a long-term plan in place for items of interest, the library swoops in to make sure it is part of it going forward.

“We can’t compete with The Library of Congress or the Smithsonian, or even private collectors with very deep pockets,” says Greek. “But people who are influential in D.C. now, mayors or political reporters who do in-depth reporting on the District, we talk to them as much as we can [about the future].”

Self-publish your own books

Digital commons librarian Emily Graves poses in front the Espresso Book Machine with copies of self published books created at the library

Digital commons librarian Emily Graves poses in front the Espresso Book Machine with copies of self published books created at the libraryTucked away in a corner of the first floor is a machine that every aspiring author, poet and writer needs to know about. The Expresso Book Machine looks like a mix between a typical copier/printer and an old-fashioned printing press.

More important than its look, however, is its function: to bring that novel you’ve written to life. Patrons can send a digital file to the library and watch a real-life, bound, paperback book pop out the other end. Library staff offer classes and personal instruction to newbies, so don’t be scared off if you’ve never self-published before.

A single copy will cost anywhere from $10-$25, depending on how many pages you’re printing. You might run up a high tab if you rely on it to mass publish, but the library does offer 10 and 15 percent discounts for bulk purchases.

Complete Records for The Washington Evening Star

Anyone who has stopped by Washingtoniana located on the third floor of the library knows that it is a veritable treasure trove of D.C. history. In addition to keeping scores of District records on housing, topography, politics and genealogy, the unit owns the complete print and photo records of The

Washington Evening Star.

For 128 years, the Star served as the daily newspaper of record in the District before finally closing in 1981. Detailed original reporting from the day accompanied by stunning black and white photos capture everything larger (and smaller) than life that passed through the District from the time of the Civil War to the launch of MTV. Nearly every famous politician, celebrity and foreign dignitary who ever passed through the city got covered by the Star, alongside the kind of bread and butter local reporting that brings the sound, smell, and feel of each era to life.

Washingtoniana has become a favorite haunt for history buffs, researchers, documentarians, and television shows (the department has provided research and records for several HBO productions). “We don’t have it all," Kenneth Despertt, special collections librarian, says, "but for lack of a better term, we’re probably the spot for the District of Columbia.”

Black History in the District

The library draws its name from a civil rights hero, and part of its mission is filling in the gaps of its black history. While most mainstream records provide detailed and accurate historical accounts of many aspects of District life, records on the city’s black population are spottier. According to Despertt, this can partially be blamed on the segregation and racism of the time.

“It’s a fact. The

Evening Star didn’t cover African American neighborhoods,” says Despertt. “Occasionally they did, but …they didn’t spend a lot of time on positive stories on African Americans.”

As a result, ad-hoc local groups had to develop and publish parallel versions of business directories, social lists and other records so that the city’s black population knew which shops they could patronize and keep tabs on who was socially important in the community. The library’s Black Studies wing and Washingtoniana have spent years piecing together these records and publications. Their collections have been used to inform books and movies on the 1968 race riots, the Tuskegee airmen and other pivotal moments in black history. Beyond that, the records are meant to document and preserve the day-to-day thoughts, practices and habits of Chocolate City.

“[These records were] a way for the African American community to say ‘Hey, we were here,’” says Despertt.

Center for Accessibility

The library’s second floor is home to a parallel world, where technology and literature are tailored for those with disabilities. The Center for Accessibility has shelves stocked with classics written in Braille, but technology has allowed the center to take its mission much farther. The center boasts dozens of software programs and hardware to help the visually, audibly and physically impaired better read books or correspondence, operate computers, and manage modern technology

“In this city, there aren’t any other libraries – even on a university level – that have some of the stuff we have,” says Bernard Harrison, library technician for the center.

Case in point: the room has a gaming center. Through a partnership with

AbleGamers, a Charles Town, West Virginia-based charity that promotes assistive video gaming, the library offers several Xboxes and other console systems for physically disabled gamers. The controls are rewired and jury-rigged to allow players to substitute large, portable buttons for a standard controller. For those with physical or other disabilities, it allows them to play more comfortably. AbleGamers spokesman Steve Spohn said the charity has similar gaming centers around the country and helps disabled gamers set up similar systems in their homes.

“It's difficult to know exactly what set up is best for everyone without giving every possibility a try,” says Spohn. “Having the Accessibility Arcade in a public library allows for the equipment to be watched over in case people need assistance, but it's a lot closer than driving out to AbleGamers headquarters in West Virginia.”

Old Maps

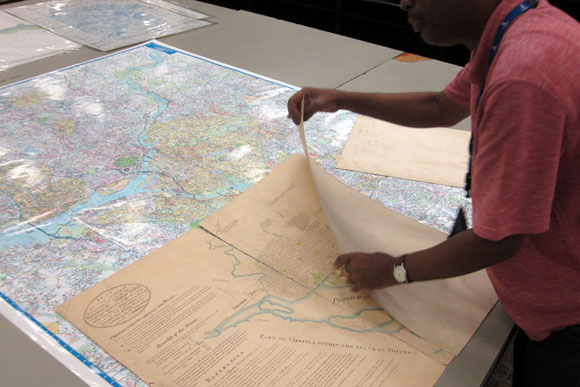

Old maps like this nineteenth century recreation of the original map of the district layout drawn by Pierre Charles L'Enfant fill the drawers and filing cabinets of Washingtoniana

Old maps like this nineteenth century recreation of the original map of the district layout drawn by Pierre Charles L'Enfant fill the drawers and filing cabinets of Washingtoniana

Maps aren’t usually classified as “wonders”, but maybe these should be! Washington D.C. has changed a lot over the years, and Washingtoniana’s maps go back to the eighteenth century. Want to view the city and its surrounding territories through the eyes of a union general at the outset of the Civil War? Or see what the layout of the city looked like when there was a giant canal running through Constitution Avenue? The library’s map collection offers endless opportunity for observing how the nation’s capital developed over the years since Pierre Charles L’Enfant drew a diamond over some swamplands between Virginia and Maryland.

The building is an architectural and historic landmark

It’s sometimes hard to stand out when you’re setting up shop in the same city as the Washington Monument, the Lincoln and Jefferson Memorials, the Ford Theater, Capitol Hill and the Smithsonian museums. Nevertheless, the MLK Jr. Library has its share of historic import. The building was designated a historic landmark in 2007 and is the only structure in D.C. known to have been designed by famed modernist architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, whose minimalist “less is more” style revolutionized the Chicago landscape. Described

at the time as "a pristine, pure structure of black steel and dark glass”, Mies van der Rohe finished the design but died before the central library was completed and before it was renamed to honor King’s legacy.

Now, more than 50 years after first opening its doors, the library believes its facilities are badly in need of an upgrade. Starting next year, the MLK library will temporarily relocate as the building

undergoes a $208 million renovation and modernization. The plans call for adding a fifth floor to the building, a new 500-seat auditorium, a café and restaurant and more than $76 million into IT and technology upgrades to ensure the facility remains state-of-the-art for years to come.

"In its current condition, the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library is an uninspiring, confusing, and poorly-configured building,” says Richard Reyes-Gavilan, executive director of the DC Public Library in an emailed statement. “After the modernization, the library will be the most welcoming and inspiring civic building in the District, offering opportunities for education, entrepreneurship, innovation, and culture.”