Visitors to Washington, DC often describe the city as very walkable, and are delighted to find they can do most of their sightseeing on foot. But residents often have an entirely different idea of what makes each neighborhood more or less friendly to pedestrians. As advocates prepare to visit the city at the end of October for the National Walking Summit, we hit the sidewalks alongside of a few locals who use foot travel as a way to explore and transform their own neighborhoods -- and lives -- for the better.

By many people’s accounting, D.C. remains one of the most walkable cities in the United States.

Contributors to travel websites, for example, regularly remark on how easy it is for visitors to get from one sightseeing location to another without the need for a car.

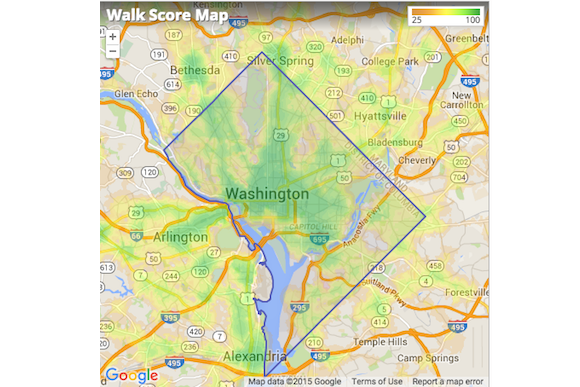

Walk Score has given the city a score of 74 (out of a possible 100) for being “very walkable” because most errands in many neighborhoods can be accomplished on foot. Going one step further, a study published by the Center for Real Estate and Urban Analysis at George Washington University in 2014 gave the city its highest ranking, noting that access to retail, food and entertainment is quite strong across many neighborhoods, including those outside the city’s official boundaries.

But those that live here often have a very different ideas about what makes the city more, or less, friendly to foot travel.

Walking as a way to network

As someone who started a business around the concept of walking the city regularly, Jessica Tunon has spent a lot of time thinking about what makes D.C.’s different neighborhoods more or less good on foot.

Some neighborhoods have better curb cuts and safer crosswalks. Some have better sight lines so you can see what is ahead. Some have nice wide sidewalks that allow you to walk side by side with a companion.

Others have dangerous tree roots that force you to only to look down while you take each step. And still other neighborhoods don’t have sidewalks at all, making a safe walk almost impossible.

In addition to safety, Tunon thinks any discussion of walkability should also include some less tangible factors, such as how appealing a neighborhood is and how many new things a person can discover there as a pedestrian.

Tunon is an entrepreneur who seeks to combine walking with community connection. Her business, Netwalking LLC, is likely the first of its kind in the United States, although she admits that she by no means invented the idea of connecting with people while on a walk. Basically, she gathers groups of people together to stroll through different neighborhoods while talking to each other in small groups or pairs.

Unlike athletic events or walking tours, “netwalking” is about building and sense of community. People should netwalk, she says, in order to experience the city where they reside in a whole new way alongside of others.

“Netwalking,” Tunon explains, “is curated networking, walking and active learning.”

The idea for Netwalking stemmed out of her dissatisfaction with traditional networking events and a desire to be more active. After suffering through a serious back injury, she had been ordered to walk regularly as a part of her physical therapy regime.

“Walking … taught me how to appreciate things, how to open up to new experiences, and move things forward,” she says.

Tunon resists saying that one neighborhood is the most walkable in the city. Her own neighborhood near Thomas Circle is great. But so is Shaw. Brookland, she notes, is full of amazing things too.

In the end, walkability is a pretty subjective thing. Men and women, she notes, often seem to think of walking very differently. As a woman she will only walk in unfamiliar areas during the day or in the morning.

Sometimes she even looks up crime rates before setting out – a practice that many men in the city might find surprising.

“I look around to see if there are women and children walking,” she says. “Sometimes if there’s only men I take a different way because I don’t feel comfortable.”

“I think a lot of things are affected by how safe people feel in their own community, and a lot of that is how walkable it is,” she says.

To make walking safer, get more kids to do it

Walking to school at Tyler Elementary

Walking to school at Tyler ElementaryAs the former PTA president for Tyler Elementary School in Southeast, Dan Traster has seen a lot of close calls between vehicles and children.

“The biggest risk to kids is traffic,” Traster says. “It’s not like we’re worried that kids are going to get kidnapped or that they’ll run into unsavory characters.”

Tyler Elementary’s student population is comprised of children who come from both near and far to attend class, because it offers a special Spanish immersion program parents find appealing, Traster explains.

In this way, the school is similar others across the District. Many city students opt for a special program or charter school outside of their neighborhood. But there are no yellow school buses to transport them there. So most students rely on either a ride from their parents or a trip on public transportation to get to class, often alongside Mom and Dad who are on their way to work.

But even though many might hop on Metro and then walk to get to school at Tyler, cars were the number one concern for Traster and his group, because parents who did drive would often double-park along the narrow streets flanking the building in order to walk their children inside. What ensued was chaotic, as frustrated commuters both on foot and in vehicles moving through the neighborhood were often darting around those double-parked cars in an erratic manner. Children were also often coming at the building from many directions and darting across the street at multiple points. Much of this took place while garbage trucks and delivery trucks tried to also squeeze by on their rounds each morning.

To find solutions, the school joined the city’s “Safe Routes to School” program, run by the District Department of Transportation.

“I hear more about traffic concerns than I do about crime and personal safety concerns by far,” says Jennifer Hefferan, coordinator of the program. So far more than 40 schools have signed on for her office’s help.

Counterintuitively, making it safer at Tyler meant encouraging more kids to walk or bike to school, because more kids on foot meant fewer drivers and cars in the mix.

Adding another bike rack helped, as did encouraging parents to form “walking busses” where one adult would supervise multiple children as they made their way from home to the school’s front door.

The school, with suggestions from DDOT, also lobbied for a second crossing guard so that multiple paths to the school could be monitored actively each day, keeping aggressive drivers at bay and encouraging students to cross only at the crosswalks.

The school also blocked off parking spaces in front of the building to include a lane where parents could drop their children off to be escorted inside by student “safety patrol” volunteers. This enabled traffic to keep flowing smoothly toward the nearby entrance to highway 695 and prevented unneeded double parking.

Now, mornings outside of Tyler Elementary have become more predictable and calm. On a recent morning parents and children could be seen flocking toward the bike racks in large numbers and waving hello to their crossing guards as they made their way to the front door. All seemed to run like clockwork.

The efficiency and increased safety has made the entire neighborhood work better, Traster says, and even those who don’t have kids have benefitted.

Like a lot of middle class people who have moved to the urban core in the last two decades, Traster says he and his wife were initially attracted to their neighborhood for its closeness to amenities, and they liked being able to commute to work on foot or via mass transit. They could choose not to drive if they wanted

But, Traster notes, he is keenly aware that not everyone has a choice. For those who can’t afford a car, a “neighborhood has always has to be walkable,” he says. “No matter what.”

Walkability equals health and confidence

Walkability equals health and confidence

Taking a thirty-minute walk once a week doesn’t seem like an insurmountable goal, but for many African American women in D.C. and around the country, it’s not easy.

“They say, ‘I’ve gone to work for eight hours, I’ve taken care of my home, I’ve taken care of my children and given to my community. I’m just done and I can’t even muster the strength to do something for my own self,” Nicole Hubb, National Field Director at GirlTrek, says.

Others also talk about being scared of crime, or having a hard time finding places where the traffic isn’t bad and the streets are accessible and have sidewalks. Some women also say they avoid walking as much as possible due to catcalling men who intimidate them or make walking repulsive.

GirlTrek, a national organization based here in D.C., is hoping to overcome some of those issues and simultaneously reverse some common health problems plaguing African American women by asking black women across the U.S. to take a thirty-minute walk once a week.

To date, more than 35,000 women have taken the group’s online pledge, although GirlTrek’s goal is to have more than a million signed on by 2018.

Part of the group’s mission involves getting women to realize that if they take care of their own health they can continue working to care for those they love for a longer time.

The group also tries to remind women what an important role walking has played in African American history and engender a sense of pride about the activity, and in 2013 hosted a walk to celebrate the life and achievements of the famous Underground Railroad Captain Harriet Tubman. The past year they also led group walks in Kenilworth Aquatic Gardens and the National Arboretum.

“While we’re out there walking we’re hoping we’ll be able to break the barriers of safety and make other women feel more comfortable doing the same,” Hubb says. “We want women to feel like their communities’ superheroes.”