Mary Tyszkiewicz is using improv to help people prepare for and recover from disasters.

Most people never think about how a tornado or earthquake could wreck their lives until they're staring one down. Similarly, most people don’t walk out of their homes thinking they could be involved in a workplace or school shooting until they’re running for cover. By that time, though, it may be too late.

But what if individuals can become prepared for life-threatening situations by associating these circumstances with something they enjoy like art? Whether they’re able to help an injured person through improv techniques or use public art to find refuge, thousands of lives could be helped or saved.

In the aftermath of disaster, art can also be used as a way to heal, understand and recover. Montgomery County artist Mary Tyszkiewicz is making this possible through

Heroic Improvisation.

Art to Prepare

While natural disasters such as hurricanes can be monitored by seasons, other life-threatening situations are less predictable. In 2001, Tyszkiewicz found herself in the midst of a chaotic scene in D.C.’s Capitol Hill neighborhood during the 9-11 terror attacks.

“I personally felt like I was okay. I was more frustrated and amazed by the amount of dysfunction,” she says.

Since then, Tyszkiewicz has researched and documented how small groups of people implement solutions in high-stakes situations. She discovered that when people are motivated by genuine care, they naturally connect to solve problems using a pattern that she calls the ‘Heroic Improvisation Cycle.’

Today, Tyszkiewicz teaches an improvisation course to get small groups--about six to 16 people--to feel comfortable using their innate abilities to solve problems. During one- to three-hour sessions, she facilitates activities like "Eagle/Bear" where participants react to situations in animalistic ways. Some participants feel awkward about playing these games, but Tyszkiewicz says that's normal. “One of the things that we say is when people are confronted by an unimaginable event, that's exactly how you're going to feel--awkward and confused. You might even feel embarrassed,” she says.

Tyszkiewicz has instructed everyone from the U.S. Navy to nonprofit volunteers. She has worked with children as well as elderly groups. No matter who you are, if you begin to build comfort around the unexpected, you’re able to act more efficiently under pressure, she says. “So if you practice and you know when something unimaginable happens you can orient yourself, you can begin to move into action and feel confident that you can do something useful.”

In some situations, the goal of surviving a disaster is getting out of harm’s way. In 2005, Hurricane Katrina left nearly 25,000 people stuck in New Orleans, occupying makeshift shelters.

In 2013, 17 public sculptures were installed throughout the city to raise visibility of “evacuspots,” locations where residents should report in case of a mandatory evacuation during hurricane season. Each steel sculpture resembles a person with a raised hand. “It’s someone saying ‘hey, I need a ride’ or ‘hey, don’t forget about me--I’m standing right here’,” says David Morris, Executive Director of nonprofit Evacuteer.

Evacuteer and the Art Council of New Orleans felt that using art was a no brainer. “Art transcends every language and every literary barrier,” says Morris. “Art is something that everyone can appreciate.”

The sculptures, designed by Douglas Kornfeld of Cambridge, Mass., are 14 feet tall and 800-pounds. They are not easily missed so residents know exactly where to report in case of an emergency.

Art to Appreciate

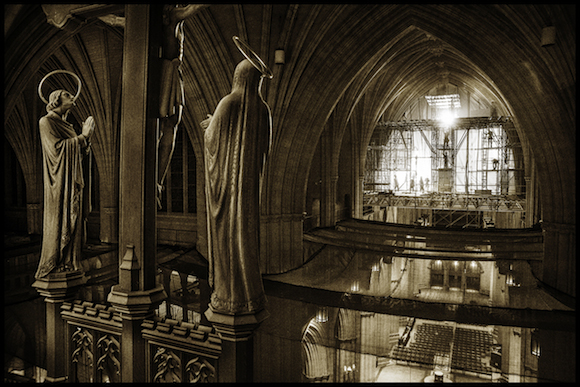

After disasters occur, the rebuilding process begins. Scaling Washington, an exhibit at the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C. provides an example of art used after calamity. A collection of large-scale images by photographer Colin Winterbottom documents the restoration of the Washington Monument and Washington National Cathedral following the 5.8 magnitude earthquake that shook DC in 2011.

Winterbottom was commissioned for the project based on his use of scaffolding, which was used on both structures during repairs (which are still ongoing in the Cathedral's case). For years, he has used similar platforms to reach vantage points that highlight the intimate details of historic buildings. This time, his photographs incorporated the scaffolds the repair team was using to get an entirely new perspective on the Cathedral.

Scaling Washington presented Winterbottom with an opportunity to tell a story. “I felt like I needed to get photos that showed what damage had occurred and then what types of repairs might be made to address those particular types of damage,” he says.

One of his favorite photos is a 360-degree, wide-angle shot of the Washington Monument taken from about 400 feet high. It takes captures the intrinsic beauty of the structure, as well as the efforts taken to repair it. “You get to take in all of the scaffolding that surrounds it and the interesting geometry of the scaffold, but then also see through the scaffold views of the city and skyline and really enjoy all of that interesting variety in a single photograph,” he says.

.jpg)

“Don’t forget about documenting and really helping people to get a better sense of the richness and interesting qualities of the structure. I hope that’s what I've been able to do through this work.”

Interested in learning more? Sign up for the third installment of Curate Your Culture, a series from the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities; a panel discussion featuring Dr. Mary Tyszkiewicz and more speakers will explore this issue in depth.